When Deterministic Pipelines Outperform Agentic Wandering

An engineered context distillation workflow consistently outperformed the latest agent.

Member of Technical Staff @ Brain Co

Member of Technical Staff @ Brain Co

An engineered context distillation workflow consistently outperformed the latest agent.

Member of Technical Staff @ Brain Co

Member of Technical Staff @ Brain Co

Our team spent time building cutting-edge agent loops for clinical rule evaluation. They were clever. They were elegant. They were also slow, expensive, and often wrong.

Modern LLM agents can call tools, plan multi-step workflows, and navigate large contexts with remarkable intelligence. Naturally, we assumed they would be the perfect fit for evaluating clinical rules over messy Electronic Health Records (EHR) data.

But after weeks of experimentation, we found that a carefully engineered context distillation pipeline consistently outperformed the latest agent frameworks across accuracy, latency, and cost metrics.

In this post, we describe our thought process behind replacing our agent-based approach in favor of deterministic systems. We make an argument for why such systems often provide better solutions in closed-world domains over advanced techniques such as agents.

One project at Brain Co. is analyzing patient records to identify all the places in a patient’s care journey where they have diverged from their ideal care pathway (e.g., a diabetic patient missing a specific eye exam). Once these gaps are identified, patients can then be connected with medical professionals to close them. This results in patients getting more targeted healthcare for their specific issues and the auxiliary benefit of incremental revenue for healthcare providers.

This is a classic “needle in a haystack” problem.

In practice, this sets up a classic problem, where tiny clues can be buried in huge unstructured documents, encounters can span many years and, unfortunately, the data is often incomplete and of lower quality.

At first glance, this seemed tailor-made for an agentic approach. The logic was simple: Give the agent the whole record, give it tools to search and filter (e.g., get_labs, search_notes), and let it "think" its way to the answer.

Agents seemed to offer two attractive benefits:

To enable this, we built out a search layer over EHR data that enabled the fast retrieval of key fields (think lab results, medications, or demographics) and configured the agent to use it to retrieve the specific bits of the patient record that the agent thought might be useful to identify gaps.

With this layer built, we were ready to test out our agentic approach.

Expectation vs. Reality Results were unexpectedly poor. Our baseline F1 score was 36%. After several engineering cycles spent on prompt tuning and tool definition improvements, we were able to push performance to 62.2% F1. but progress stalled well below what would be a useable system in production.

Across these iterations, a pattern emerged. Each agent improvement increased performance incrementally, but these gains were expensive. Every step added latency, cost, and variance.

When we went back to the drawing board, we started to consider why this strategy didn’t work. We realized our problem wasn't model intelligence, it was architectural. At that point, we stopped asking “How do we make the agent smarter?” and started asking, “How much agency should we delegate to models?”

By handing the entire workflow to an agent, we forced the model to re-derive its search strategy every single time. The agent had to decide what to look for, how to look for it, and when to stop. This introduced:

Agents excel in tasks where they need to perform external retrieval or acquire new knowledge to make decisions. However, in our case, all the relevant information was already present in the patient record.

We realized that we were using this agentic approach as a roundabout way to prune the information we were passing to the model.

Through shadowing clinicians, we knew there was a general order of operations taken to make these decisions manually. For a given rule, a doctor would:

Agentic tool use allows models to query for this information, but turning this procedure over to agents meant the agents had to "think through" what information was relevant each time it was called.

This gave the agent too much free reign. It meant agents often failed to determine what was relevant, wasting compute on superfluous information. It introduced significant stochasticity and increased latency—two factors that made iterating on the approach nearly impossible.

As we analyzed why the agentic approach wasn't working, a simpler approach emerged.

We realized that we had conflated the messiness of the data with the complexity of the reasoning. While a patient record is an 'open world' of unstructured noise, the clinical rule itself is a closed-world problem.

For a diabetic eye exam rule, the set of relevant evidence is finite and known in advance (e.g., ophthalmology notes, specific CPT codes). We didn't need an agent to discover which fields mattered; we only needed to extract them from the noise.

This gives the LLM a clean, compact context, allows for deterministic decisions, and minimizes the search space. Effectively, we split the problem into two distinct, independently reviewable tasks:

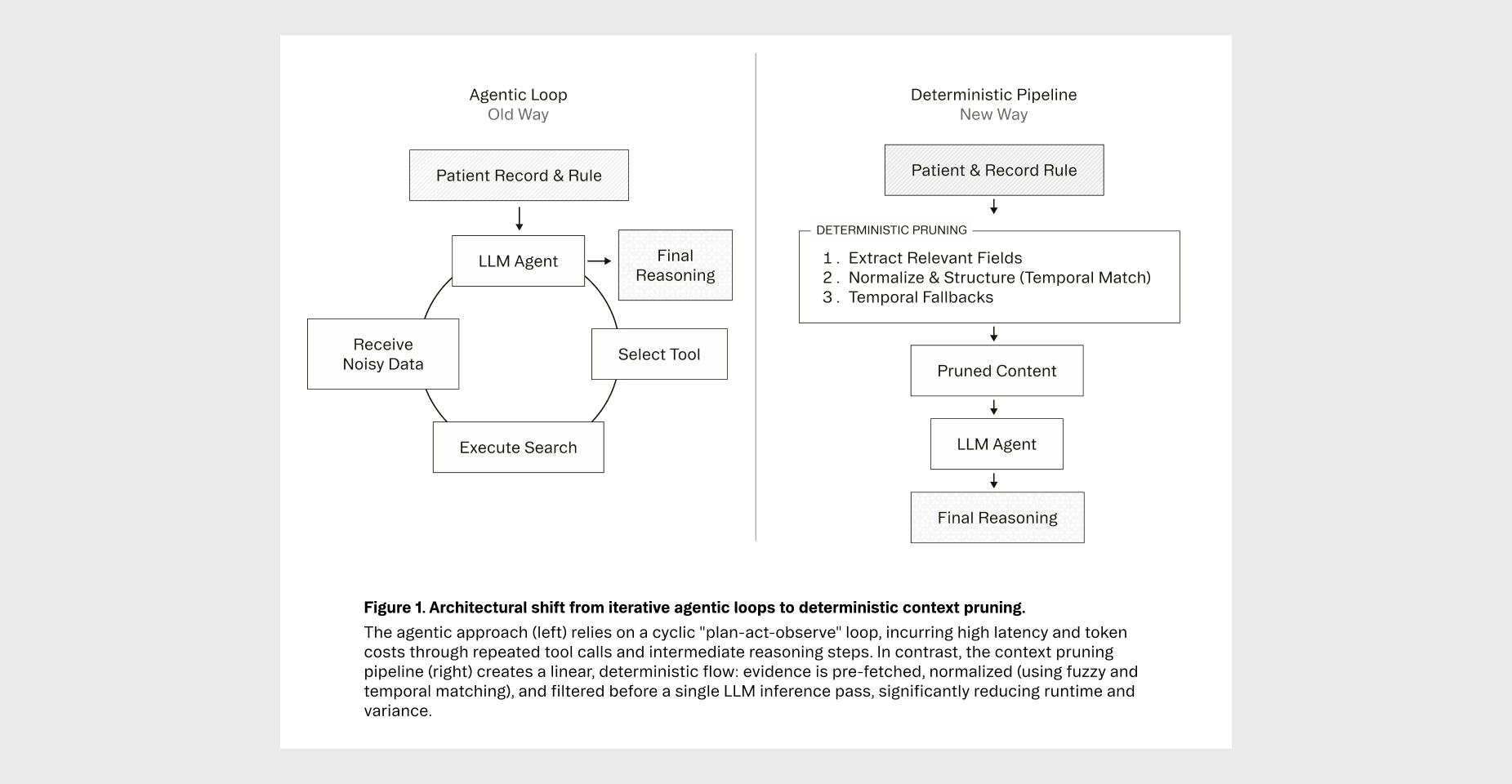

As seen in Figure 1, here is how our Context Distillation algorithm works:

Step 1: Extract Relevant Evidence For each rule, we identify the specific data types that matter—lab values, medication histories, diagnosis codes, and encounter summaries. We extract no more and no less.

Step 2: Normalize and Structure Snippets Once extracted, we normalize the structure through targeted, disease-specific evidence selection. We employ a combination of matching algorithms optimized for different resource types:

Step 3: Temporal Fallbacks When the aforementioned strategies do not yield results (perhaps because the patient never received the relevant treatment), we ensure the LLM still has data to work with through fallbacks filtered only by time.

We then sort by temporal relevance (most recent first), apply category-specific limits, and deduplicate objects to prevent redundancy. This exposes only rule-relevant evidence to the LLM while maintaining referential integrity.

Step 4: Pass Pruned Context to the Model Finally, we pass the pruned context and the rule to the model. This creates one clean input and one clean output. No tool calls. No agent loops. Just full transparency and auditability.

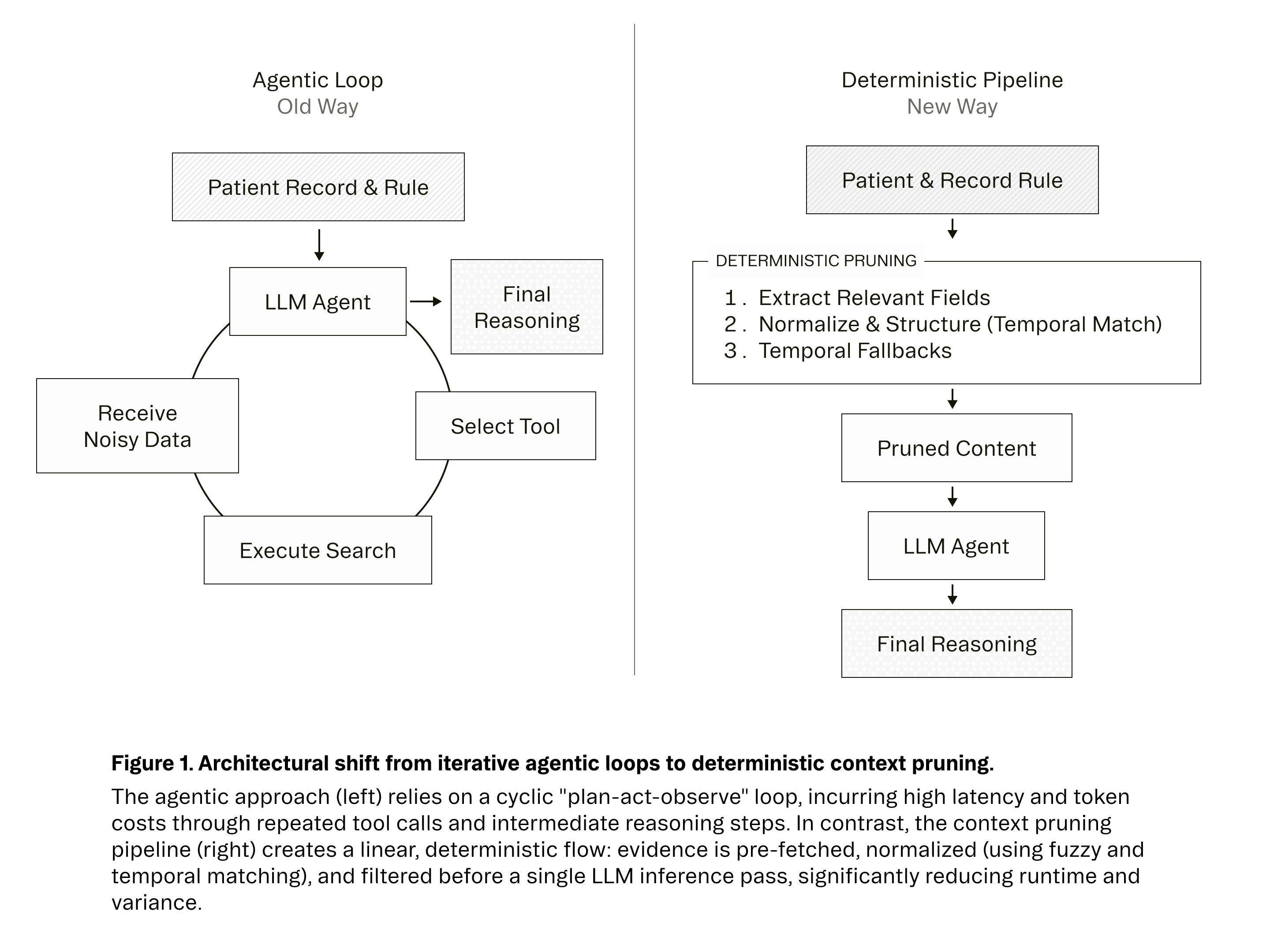

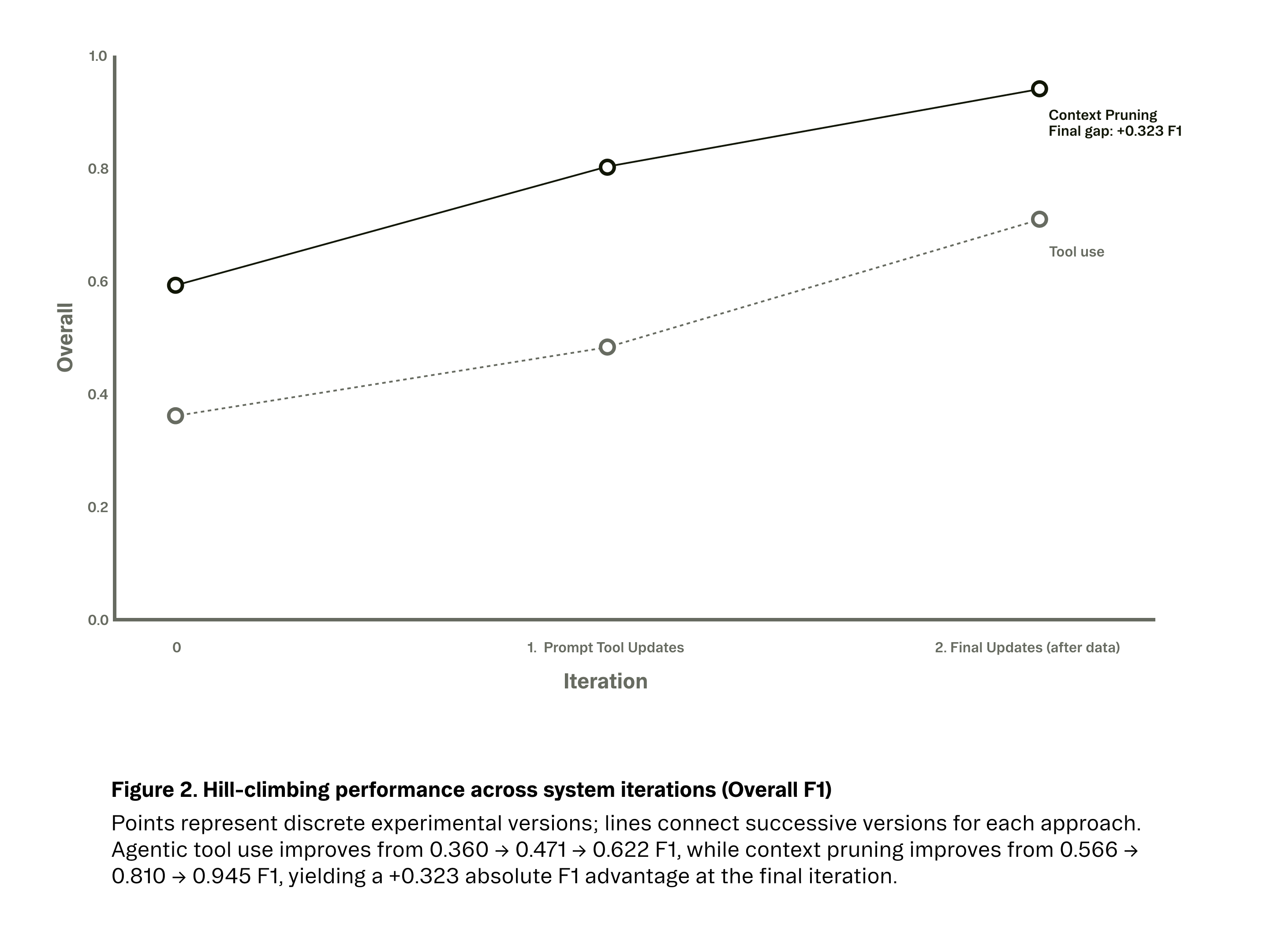

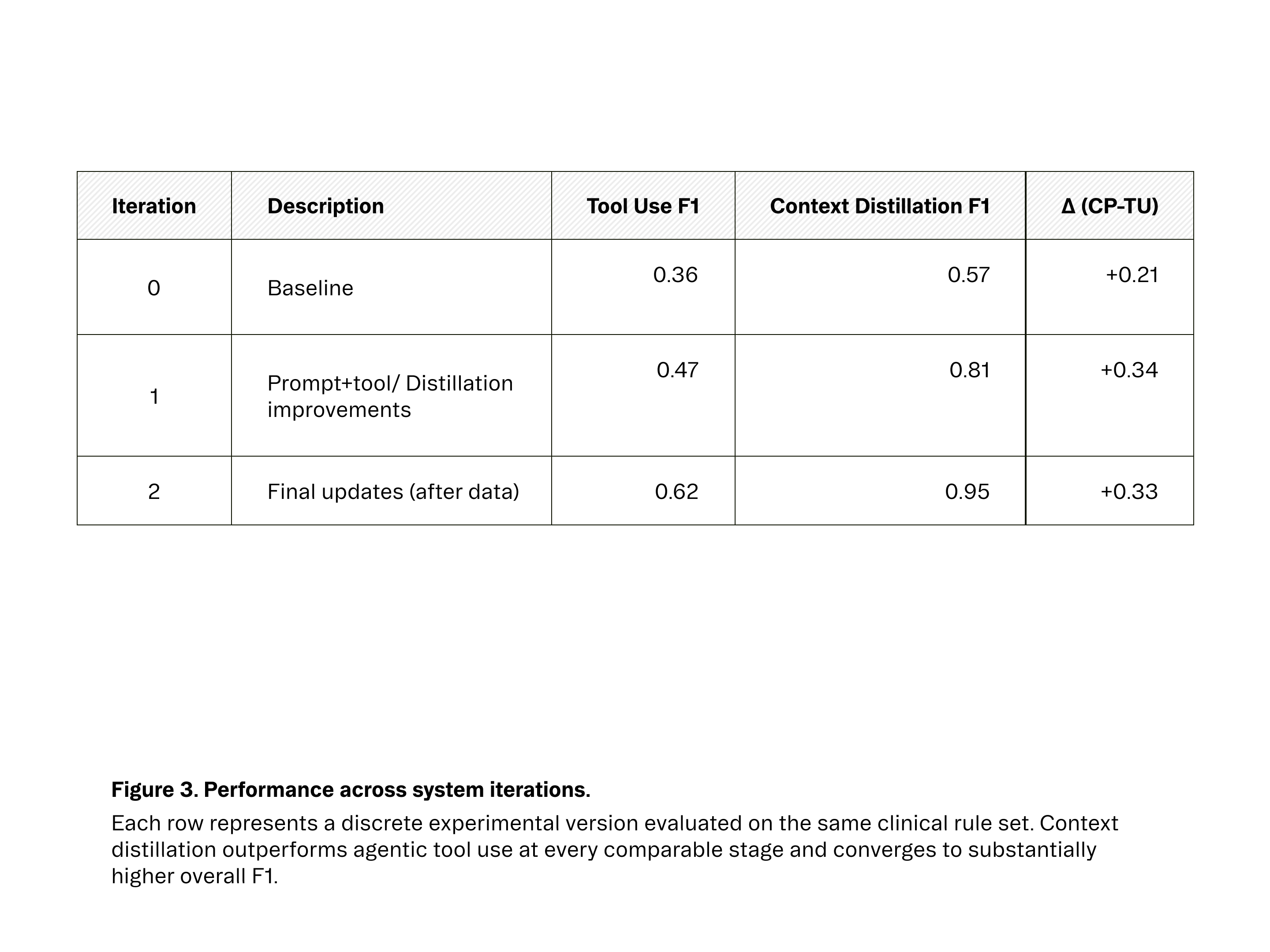

Once we integrated this context distillation approach, the impact was immediate. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, performance improved across experimental iterations for both approaches, but plateaued much earlier for agentic tool use. While our best agentic system peaked at 62.2% F1 after multiple rounds of tuning, the context-pruned pipeline surpassed 80% F1 in its first refined version and reached 94.5% F1 after incorporating higher-quality evaluation data.

These gains were not confined to a single disease or metric. The same architectural shift produced consistent improvements across accuracy, latency, and cost:

None of this is an indictment of agents, they remain enormously valuable. They just weren't right for our task.

Agents shine when you truly need exploration or external knowledge:

As we expand into disease areas with more ambiguous clinical patterns (e.g., rheumatology, oncology), agents may again become the right tool. But for chronic conditions like diabetes, the protocols are well-defined even if the data is messy. The rules are crisp: if specific evidence exists, the gap is closed.

In this landscape, asking an agent to 'explore' the record introduces unnecessary variance. When the destination is known, you don't need a scout; you need a precise extraction pipeline.

Constraints beat cleverness when logic is deterministic.

Our data was messy and inconsistently structured, so we thought agents were best equipped to explore it. However, clinical rules are closed-world problems with a finite set of relevant evidence. In this setting, building tools to deterministically retrieve this evidence outperformed asking agents to re-derive what clues to look for and how to find them. We learned that reliability doesn't come from making the model smarter; it comes from aligning the architecture with the strict requirements of the domain.

Key Takeaways:

Show the model only what matters.